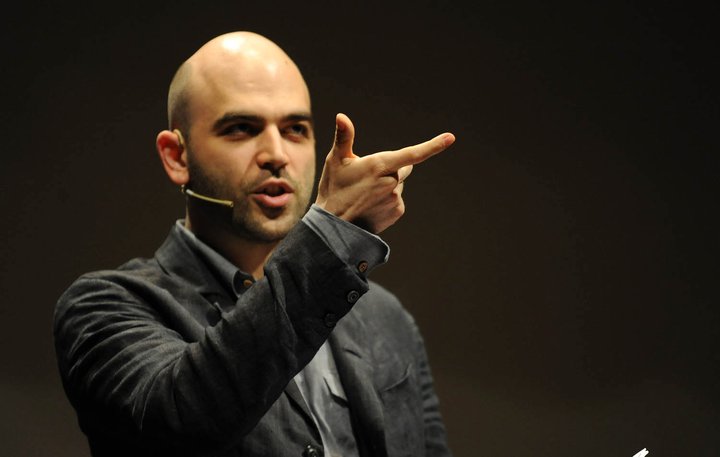

Roberto Saviano / Journalist and writer

“I have become accustomed to the idea of death. What really frightens me is having to live like this forever.”

Miguel Mora 25/04/2016

En CTXT podemos mantener nuestra radical independencia gracias a que las suscripciones suponen el 70% de los ingresos. No aceptamos “noticias” patrocinadas y apenas tenemos publicidad. Si puedes apoyarnos desde 3 euros mensuales, suscribete aquí

Roberto Saviano (Naples, 1979) is an exceptionally talented and courageous writer and investigative journalist. He is the man who investigated and told the story of the Camorra from the inside when he was 25 years old in the superbly written and fictionalized investigation titled Gomorrah. The book travelled around the globe (2 million copies were sold), became a film and a TV series, and ultimately condemned the young writer twice over: first as an immediate global celebrity – and therefore not without suspicion and jealousy –, and then with the arrival of the fatwa of the Casalesi clan, who after reading the book declared him an enemy to be eliminated.

It has been nine and half years since that death threat. From 13rd October 2006 onwards, Saviano - described by Umber Eco as a ‘national hero’ – has lived in hiding and protected by the Italian government. But even so he has continued to work. Two years ago he published ZeroZeroZero, an exhaustive investigation into cocaine trafficking around the world, in part centring on Los Zetas, the Mexican drug cartel lead by El Chapo. As for Saviano’s destiny, it seems that the dye is cast. A copy of the book – soon to be turned into a film - appeared several weeks ago in El Chapo’s hideout: the boss left it on his bed when trying to escape his second arrest.

In this interview, conducted via e-mail, Saviano explains his feelings after this finding, and warns that Spain is still the entry point for cocaine in Europe, a paradise for European and American mafias, and the place chosen by El Chapo for the Los Zetas European setup.

What did you feel when you saw ZeroZeroZero on El Chapo’s bed in the cave?

At first I could not believe it: when you see your book on the bed of the world’s most powerful drug lord, among the objects he abandoned when trying to escape, it is a little unsettling. But I have to say that the shock lasted just a few seconds: I have been studying mechanisms of crime for a long time, and I have learnt bosses always try to know what is being said about them, how they are described, how they are portrayed. It is a mistake to think that drug lords are just illiterate criminal beasts – as they are usually depicted in American literature and cinema. It is a very superficial partial view: they are also experienced businessmen who read, investigate and analyse, and want to know what the world thinks about them. Furthermore, a book or a film about them receiving international attention can cause them numerous problems by raising awareness both in the public and the media and this attention is not good for their business, which functions better when they remain in the shadows, in silence, away from the harsh glare of media spotlight.

Something similar has already happened with Gomorrah, which also appeared in the hideouts of the Camorra capos. Did you have then the same feelings as you do now?

Yes, they found Gomorrah in the bunker of Michele Zagaria, a previous boss of the Casalesi clan, and later on in that of Francesco Barbato, the boss of the new generation. And not only that, after its publication, it was the most widely read book in the prisons of the South of Italy: camorrists wanted to know what I had said about them and how I presented them to the world, outside the territory where everybody knows them. This time, like then, my first reaction was the feeling that my work had been contaminated, as if it had been brought to the attention of the wrong person. Furthermore, there were already several books, monographs and documentaries about El Chapo, and so I wondered why he would only be reading my book… The truth is that I have no idea, but I have heard wildly differing hypothesis: some say his lawyer wanted him to read it to gather more information about me and what I had written about him after his 2014 arrest, when I declared to the Mexican media the need and urgency to extradite El Chapo to the United States; some believe that the book really belonged El Chapo’s son, who had seen me in a CNN interview; and others even assume that it could have been a present from Sean Penn during the meeting they had a few days before he was arrested again, as it was the American edition, and not the Mexican one, which was found in the cave. It may be that since ZeroZeroZero was on the bestseller list for quite a considerable time in Mexico, El Chapo was curious to know what I had written, as he is one of the main characters of the book.

How has the discovery of book affected your safety? Are you still receiving protection from the Italian government? Is it safe to say where you are now?

In Italy I have lived under protection 24 hours a day, for 9 years and a half now. It is a difficult life because you are often confined in the police headquarters. When you live under protection even going for a walk on the street can be a problem, it is as if you are starved of oxygen. That is why I try to spend a lot of time abroad, where in some cases I can be unaccompanied because I am given a false identity. It is not that I feel less secure since the finding of the book in the cave, but I know my life is going to get a little more complicated. After the news, when I landed in the United States, I was detained at customs because the officers wanted more information about the finding, although I knew as much as they did. They wanted more details because there was a rumour that the copy of ZeroZeroZero found in El Chapo’s cave was signed by me, which is unequivocally untrue.

Are Mexican drug traffickers related to European mafias? What are their links, their businesses and their methods?

Apart from a number of investigations proving the collaboration between Colombian organizations and the Calabrian Ndrangheta so that the cocaine arrives in Europe, there are proceedings that demonstrate the connection between Los Zetas and the Ndrangheta, not only to ensure the cocaine reaches Italy, but also to New York and Canada, where the Calabrians have their cells and are extremely powerful. The collaboration with one another is fundamental mainly because there is a very extensive cocaine network managed by different groups in several countries; besides, in the countries with very powerful mafias, as is the case of Italy, it is difficult for a foreign organisation to enter into a foreign market without reaching an agreement with local mafias. This has given rise to these collaborations: it is better to divide up the business than to see it disappear altogether and running the risk of a war with another organisation.

In the book you describe in detail the connection between Latin American drug narcos and Spain. Does it already exist? Are they already here?

Spain is still the entry point for cocaine in Europe. It is a privileged stop-off for the cocaine coming from South America, mainly by boat. Mexican cartels have tried to move in on the European market that was previously under the control of Colombian cartels (the Mexicans controlled the North American market). An investigation carried out a few years ago by the FBI and the Spanish police, ‘Dark Waters’, revealed the Sinaloa cartel planned to extend the market to Europe to sell cocaine directly to the old continent, via Spain, which would have been used as the entry point to deliver the drug on this side of the Atlantic. The cartel had sent some of its members to Madrid to handle the business, including Chapo Guzmán’s cousin. According to the information I am gathering now, Mexican drug traffickers are persevering with the idea of taking over a part of Europe, capitalising on the increasing weakness of Colombian drug barons. Nowadays Mexico is the heart of world drug-trafficking.

In Gomorrah you wrote that Spain is Costa Nostra for the Camorra. You have always declared that the Spanish criminal law system protects mafias and does not fight against them. Why?

Spain is like a ‘second home’ for all European criminal organisations. Not only is it an excellent base to run the drug business with Latin America and the North of Africa due to its geographical location, it also is an excellent place to end up in prison, especially if you are an Italian criminal. In Spain there is no ‘harsh prison’, the regime so feared by the Italian mafia and drug-traffickers because privileges are so severely limited. The absence of such restrictions means criminals are allowed to see their relatives frequently and to live in dignity and without harassment. When Pasquale Locatelli - one of the biggest cocaine brokers that has ever existed in Europe - was in prison in Spain, as is reported in the Box investigation carried out by the Guardia di Finanza of Naples, Locatelli himself as well as his family emphatically refused his eventual transfer to Italy, which finally happened last year. Spain is also one of the favourite places of Italian fugitives to seek refuge: Pasquale Locatelli was arrested twice, in 1994 and in 2010. Giuseppe Polverino, capo of Marano’s homonymous clan who is on the list of the most dangerous Italian fugitives, was arrested in March 2012 in a small house in Jerez de la Frontera. He was in charge of the narcotics supply in the axis of Marano in Naples and the South of Spain. Therefore, there are many reasons why Spain is the locus amoenus of European criminals. But Spain is not the only European country that in some way involuntarily protects the mafia. We need to think about how many countries do not categorise association with the mafia as a crime in their legislation: those who in Italy are defined as mafia and who are subject to certain legal proceedings in Italy, are just regarded as common criminals in other countries. This significantly limits the struggle against the mafia. Greater international coordination and collaboration is required.

Soon it will be the tenth anniversary of the Camorra’s death threat to you. How have your situation and your life changed?

Everything has changed. Yes, in October I will have been living under police protection for ten years. Armoured cars and policemen around me all the time… It is hard, but I know it is a privilege, in México dozens of journalist have been killed, in Saudi Arabia you get arrested if you have a blog… I am alive and I can continue writing; somehow you are very lucky if you can do so nowadays. Those who write do not realize that in many other places it is one of the most dangerous activities.

Do you think it is going to be a life sentence?

I hope not, but I have no evidence to the contrary. I have heard so much about my death sentence that I have got used to that idea. What really scares me is to have to live like this forever.

Can a journalist in hiding practise journalism?

My way of being a journalist has changed a lot since I’ve been under armed-guard. While I was writing Gomorrah, I could freely ride my motorbike around Casal di Principe, the territory of the most powerful group of Camorra, or the most dangerous neighbourhoods of Naples, and I could also work under cover because no one knew my face. Today, apart from security issues, that severely limit my freedom to move around and prevent me from visiting dangerous places, I also have the problem of being well known, making it impossible for me to do my research undetected. I live with the paradox of being very well known and living life as a recluse due to the 24 hour armed guard, two things that seem an oxymoron: it is something people find difficult to understand and accept, and that generates mistrust. Once, a lady stopped me at the airport and said: “What are you doing here? Can you go out? I pray for you every day…” For the majority of people, as someone condemned to death, I should have died, but it is strange for a dead person to write books, to be on TV or just to take a plane. It is a short circuit, which often gets to some journalists or politics, who don’t particularly like me, maybe because we have different ideologies. But returning to my work, in all these years of an almost ‘military’ life, under armed-guard, I have had the possibility of meeting law enforcement agents, magistrates in Italy and overseas, and gaining first-hand information which otherwise would has been very difficult to access. Finally, I think that working as a journalist consists not only in going to the source, but also in putting all the pieces together, in analysing, in giving a context. Investigative journalism is just that: without analysis, without the study of mechanisms, without a broader perspective – which is what I tried to attain in ZeroZeroZero -, there would be no genuine research, only a sterile list of facts. This is of course essential, but can only ever be a starting point for those practicing this profession.

Translated from Spanish by Tony Keirle and Paloma Farré

Roberto Saviano (Naples, 1979) is an exceptionally talented and courageous writer and investigative journalist. He is the man who investigated and told the story of the Camorra from the inside when he was 25 years old in the superbly written and fictionalized investigation titled Gomorrah. The book...

Autor >

Miguel Mora

es director de CTXT. Fue corresponsal de El País en Lisboa, Roma y París. En 2011 fue galardonado con el premio Francisco Cerecedo y con el Livio Zanetti al mejor corresponsal extranjero en Italia. En 2010, obtuvo el premio del Parlamento Europeo al mejor reportaje sobre la integración de las minorías. Es autor de los libros 'La voz de los flamencos' (Siruela 2008) y 'El mejor año de nuestras vidas' (Ediciones B).

Suscríbete a CTXT

Orgullosas

de llegar tarde

a las últimas noticias

Gracias a tu suscripción podemos ejercer un periodismo público y en libertad.

¿Quieres suscribirte a CTXT por solo 6 euros al mes? Pulsa aquí